Here's an article from the Onion - the satirical newspaper - that prompted me to write this in the first place:

Many people have asked me recently about what the mood is like in Japan now that North Korea is, apparently, a nuclear power. After all, it's the Japanese who have the most to fear from N. Korea; with the North Korean missile tests, the Japan has already had two shots fired across its bow. I read in the NY Times online or the BBC News that there's a great fear of nuclear proliferation, of what a maniac like Kim Jong Il might do. The Koreans - even the South - still carry a great deal of resentment, to say the least, against the Japanese over what happened during WWII, and the consistent refusal of the Japanese government to accept responsibility for its wartime actions.

Considering the amount of basic hysteria across much of the US about terrorist attacks - even in places (the entire Midwest?) no terrorist could possibly have heard of, let alone care to target - I thought there would be some level of popular discourse about this situation. I came to work the day after the announcement of the testing of a nuclear weapon. I waited to hear teachers commiserate over their anxiety, or students to ask questions about what would happen, or the principal to make some sort of statement. I waited entirely in vain. The only announcement at the morning meeting was to report on a bicycle accident and remind students to be careful on their way to school. Talk between teachers was as rare as always and as always centered around classes and the monotony of grading papers. Everyone acted like they hadn't heard anything at all, to the extent that I wondered if in fact they hadn't heard anything at all.

Finally, sitting at the computers and reading the newspaper, I brought it up with the Beach Boys Sensei and another teacher. I asked them if they were aware of what was going on, and how they felt. They said of course they knew about it, but responded, "what are we going to do about it?"

And that sort of shrugging off really typified for me the attitude of most everyone here regarding politics. If people are aware of politics at all, they seem aware of it in a totally peripheral way. Politics seems to be to most Japanese, something that happens off in Tokyo. Politics is the business of politicians, and these decisions are to be made by the people off in those governmental buildings. They'll take care of it, so it isn't necessary for people to have opinions either way on issues; they just need to do their jobs.

And know I'm coming from a country where the majority of people don't even vote, and even if they do, it's often based on party lines or without a clear understanding of the issues. Still, I have a hard time imagining Bush getting angry at representatives from his party that don't fully support him and fielding new candidates in an election for their districts that don't even live in the areas. But that's what Koizumi did in the last election; he blacklisted several representatives and sent actresses and businesspeople to run in areas of Japan they might not even have visited before. And they won. People voted for candidates that don't even live in their areas or know anything about them to represent their hometowns and their interests in parliament. That seemed to me to be a pretty clear indictment of how seriously people take the idea of representative government here.

The LDP, roughly equivalent to the Republican party in the US, has been the ruling party here for almost 50 years, with only one brief interruption. We complain about our two party system being inadequate for a real democracy; the system here is a joke. The same giant conglomerates that ran Japan before and during WWII - the equivalents of the huge German companies basically - were never dismantled or run through any sort of process comparable to the de-Nazification in Germany. The current top politicians are either holdovers or descendants of the same people who drove the country right into war before and never recanted afterward. The Emperor has never been held responsible for anything he did, so how can anyone else be, really?

These things shock me, but leave no impression on most people it seems. There was no political discussion going on at Waseda when I was studying there; no protests, no activism, no general awareness of issues at all, really. The complete disassociation with what's going on in their country by people here leaves them dangerously open to being led into another bout with disastrous nationalism. With the same sort of people in power as before WWII, it's just fortunate that the current goals of the government seem merely economic.

Tuesday, December 19, 2006

Saturday, December 02, 2006

Christmas with the heathens

Next week is final exams so I've been taking it easy on the kids and teaching classes about Christmas. I play Christmas songs (Nat King Cole - The Christmas Song mostly, since that's the only xmas song I can stand to listen to the requisite 40 times or so I will in the course of teaching all the first year students) and the kids try to fill in missing words on lyric sheets; I pass out candy canes and have them write letters to Santa. One day, a teacher asked me to talk a little more about the origin of Christmas - assuming, I guess, like all Japanese do about all Americans, that I am a Christian of deep faith. I had toyed with the idea in the beginning, but thought it might come off as proselytizing, but on further reflecting, realized clearly there no harm in merely talking about religion.

So after listening to Nat King Cole for the umpteenth time, I write the word "Christmas" on the board and ask the kids what they know about the holiday. They volunteer and I list words like toys, Santa, reindeer, Christmas tree, etc. "Okay," I say, "so maybe when you think of Christmas, these things come to mind."

"But, does anyone know why Christmas is a holiday?"

Blank stares.

I think that maybe they just didn't understand the question, so I rephrase it: "Does anyone know what happened on Christmas?"

Blanker stares.

I pause and, stifling a laugh, take a deep breath. Then I turn to where I've written "Christmas" on the board and underline "Christ" several times. I turn back to the class and ask, cautiously this time, "Do you know who this is?" I wince a little for a few seconds as if anticipating a blow, but fortunately one of the kids says the Japanese name for Christ (kirisuto), and I don't have to freak out completely.

"Okay great, Christ, yes. Jesus Christ. (in a fashion taking His name in vain) Jesus Christ, yes. Now, what happened to Jesus Christ on this day?"

A student raises a hand tentatively and says in Japanese, "That's when he died, right?"

I run my fingers through my hair quite hard. "No." I smile. "In fact, the opposite thing happened. And speak in English."

Another says, "Ah, it's his birthday."

"Yeah, more or less. So, let me tell you the story of his birth."

It turns out that they don't really study world religions, at least not until their junior or senior year of high school. I have a hard time comprehending that these sophomore kids at a high-level high school don't know basic facts about the largest religion in the world, since I learned about Shinto in my 7th grade history class. This is kind of insane. So I decide to right this wrong. I am here to bring them the good news, as it were.

I whip out some Christmas picture books and proceed to tell the story of the Nativity. In the course of trying to explain to the kids why it was such a big deal that a baby was born in a manger in some far-off place thousands of years ago, I come to appreciate to an extent how ridiculous missionaries must feel on their first day off in some African village. Trying to explain a religion to someone completely unfamiliar with the stories just reveals how ridiculous they can sound. I see a new expression of bafflement cross the faces of the students for each phrase like "son of God" or "angels" or "three kings" that comes out of my mouth. By the end of the story, I am rather baffled at what's coming out of my mouth as well. You'd have to be a person of unshakeable faith to speak in any way convincingly about these things without feeling a bit silly or embarrassed. I am not that person.

This reaches a sort of crescendo while I'm using the tiny statuettes of the Nativity scene to act out the different character's parts. After a long explanation of the relationship between Mary and Joseph where I've been holding up their two figures, I actually look down at what I'm holding and see that in fact what I'm holding is not Joseph but some random shepherd. Upon closer inspection, I realize that on top of the general discernible differences between the two figures, the shepherd actually has a damn sheep hung around his neck. So, not only have I been telling a rather sacrilegious story about the unconsummated love of Mary and one shepherd from Bethelehem, but I've convinced all the kids that Jesus' father walked around with a sheep strung around his neck at all times. I break and just laugh really hard.

I give up in the end and just have them write their letters to Santa. I tell them about Santa's list; presents for the good children and coal for the bad. This is much easier to talk to the kids about. It doesn't make me embarrassed as an American or feel ridiculous at all. As silly as Santa's story is, at least we all agree none of it is true.

So after listening to Nat King Cole for the umpteenth time, I write the word "Christmas" on the board and ask the kids what they know about the holiday. They volunteer and I list words like toys, Santa, reindeer, Christmas tree, etc. "Okay," I say, "so maybe when you think of Christmas, these things come to mind."

"But, does anyone know why Christmas is a holiday?"

Blank stares.

I think that maybe they just didn't understand the question, so I rephrase it: "Does anyone know what happened on Christmas?"

Blanker stares.

I pause and, stifling a laugh, take a deep breath. Then I turn to where I've written "Christmas" on the board and underline "Christ" several times. I turn back to the class and ask, cautiously this time, "Do you know who this is?" I wince a little for a few seconds as if anticipating a blow, but fortunately one of the kids says the Japanese name for Christ (kirisuto), and I don't have to freak out completely.

"Okay great, Christ, yes. Jesus Christ. (in a fashion taking His name in vain) Jesus Christ, yes. Now, what happened to Jesus Christ on this day?"

A student raises a hand tentatively and says in Japanese, "That's when he died, right?"

I run my fingers through my hair quite hard. "No." I smile. "In fact, the opposite thing happened. And speak in English."

Another says, "Ah, it's his birthday."

"Yeah, more or less. So, let me tell you the story of his birth."

It turns out that they don't really study world religions, at least not until their junior or senior year of high school. I have a hard time comprehending that these sophomore kids at a high-level high school don't know basic facts about the largest religion in the world, since I learned about Shinto in my 7th grade history class. This is kind of insane. So I decide to right this wrong. I am here to bring them the good news, as it were.

I whip out some Christmas picture books and proceed to tell the story of the Nativity. In the course of trying to explain to the kids why it was such a big deal that a baby was born in a manger in some far-off place thousands of years ago, I come to appreciate to an extent how ridiculous missionaries must feel on their first day off in some African village. Trying to explain a religion to someone completely unfamiliar with the stories just reveals how ridiculous they can sound. I see a new expression of bafflement cross the faces of the students for each phrase like "son of God" or "angels" or "three kings" that comes out of my mouth. By the end of the story, I am rather baffled at what's coming out of my mouth as well. You'd have to be a person of unshakeable faith to speak in any way convincingly about these things without feeling a bit silly or embarrassed. I am not that person.

This reaches a sort of crescendo while I'm using the tiny statuettes of the Nativity scene to act out the different character's parts. After a long explanation of the relationship between Mary and Joseph where I've been holding up their two figures, I actually look down at what I'm holding and see that in fact what I'm holding is not Joseph but some random shepherd. Upon closer inspection, I realize that on top of the general discernible differences between the two figures, the shepherd actually has a damn sheep hung around his neck. So, not only have I been telling a rather sacrilegious story about the unconsummated love of Mary and one shepherd from Bethelehem, but I've convinced all the kids that Jesus' father walked around with a sheep strung around his neck at all times. I break and just laugh really hard.

I give up in the end and just have them write their letters to Santa. I tell them about Santa's list; presents for the good children and coal for the bad. This is much easier to talk to the kids about. It doesn't make me embarrassed as an American or feel ridiculous at all. As silly as Santa's story is, at least we all agree none of it is true.

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

Student life at Hamanan

Recently I set up a blog for the students in the English club at my school. I wish I could say it's off to a rousing start, but that would a little too generous...anyways, it is certainly off to a start of some kind. Perhaps a bemusing one?

Hamanan English Club blog

The students were asked to write short self-introductions, which prompted stories about car accidents, "soft-ball tennis," BAGELs, and PSP; not ordinary topics during first conversations.

Anyways, I'm going to try to get them to write a little something every week. I'm hoping it will, aside from allowing them a measure of self-expression not allowed, let alone encouraged, in their other classes, let others see the general lives of students here. Whether that will be interesting or depressing remains to be seen. Feel free to check it from time to time.

Hamanan English Club blog

The students were asked to write short self-introductions, which prompted stories about car accidents, "soft-ball tennis," BAGELs, and PSP; not ordinary topics during first conversations.

Anyways, I'm going to try to get them to write a little something every week. I'm hoping it will, aside from allowing them a measure of self-expression not allowed, let alone encouraged, in their other classes, let others see the general lives of students here. Whether that will be interesting or depressing remains to be seen. Feel free to check it from time to time.

Saturday, November 11, 2006

The Yellow Menace

A couple weekends ago I had another class at the local community center with the older Japanese. Typically, I give them a few topics to cover in a free conversation in groups while I walk around and monitor them, answering questions or trying to keep the talk flowing. For the second half of the class, we have some sort of structured activity: the introduction of new grammar or vocabulary, a game, etc.

I decided that day we'd have a debate, which we've done a few times before. Though their English levels vary considerably from near-fluent to near-mute, since they're all adults, they generally have something to say which makes a debate of some sort possible for everyone. I broke them up into groups again and gave them a couple topics.

One of the big news stories recently has been the Imperial Succession. In short, the Crown Prince and his wife had been unable to produce a male heir to inherit the throne, putting the succession in doubt. They do, however, have a daughter, so some people argued for a changing of the law of succession to permit the daughter to become Empress. This was the subject of some controversy because, though Empresses are not unknown in Japanese history, the actual male line - they say - has never been broken for some 1500 years. This debate was just settled recently however, when the Crown Prince's younger brother and his wife appeared with a son of their own, ensuring the safety of the succession.

As an American, I am kind of mystified and bemused at the idea of a monarch, and it seemed to me that most of the younger Japanese people I know are pretty apathetic about the whole issue, but I was curious what the older generation might think. After all, most of them lived when an Emperor still had power and apparently the institution still has meaning for them; it's always grandmas out in the crowd waving at the Emperor when he holds forth.

So for one of the topics, I asked them to talk about whether "Women should be allowed to become Emperor." I predicted an interesting talk about whether modern equality should trump traditions. I was very surprised however, as the debate they actually had quickly evolved into one over whether the Imperial system should continue at all - and most everyone said "No."

As it turns out, the Emperor currently receives a yearly stipend of several million dollars from the government. This, despite the fact that his role is entirely ornamental, and he is of course already quite wealthy due to extensive property holdings. Several women in the class were quite vehement in their displeasure of paying through taxes the salary of a man who "doesn't do anything" and yet lives in a huge complex completely isolated from the public. Others went even further, saying that the Imperial system itself is ridiculous and should be dismantled. The only dissenting opinion was the one man there that day, who said that the Emperor should be retained as a symbol of Japan. The women all disagreed though, saying they felt no connection for the Emperor, even as a symbol.

After the Japanese surrender, there was a debate among the American occupation forces about the future of the Imperial system. In the end, MacArthur and the Americans decided to keep the institution, albeit stripping it of its powers. MacArthur also refused calls to try the monarch for any responsibility in the war. He believed that any attempt to remove the Emperor would cause upheavals in Japan. Why? Because he, along with other Japan "experts", thought the people here were fundamentally incapable of thinking for themselves, and they could not have democracy here without the imperial system. They bought into the propaganda of the wartime government of Japan of the people as blindly obedient to the Emperor, and also believed in the myth of all the yellow people in general as ant-like followers.

In the end, it seems this was another example of taking the public front of a government for the feelings of all its citizens. The government talks about the respect and love people had for the Emperor, and I simply assumed that they believed exactly what the government said. I found that I still harbored some of the same patronizing views of people here as Americans did in the past.

I decided that day we'd have a debate, which we've done a few times before. Though their English levels vary considerably from near-fluent to near-mute, since they're all adults, they generally have something to say which makes a debate of some sort possible for everyone. I broke them up into groups again and gave them a couple topics.

One of the big news stories recently has been the Imperial Succession. In short, the Crown Prince and his wife had been unable to produce a male heir to inherit the throne, putting the succession in doubt. They do, however, have a daughter, so some people argued for a changing of the law of succession to permit the daughter to become Empress. This was the subject of some controversy because, though Empresses are not unknown in Japanese history, the actual male line - they say - has never been broken for some 1500 years. This debate was just settled recently however, when the Crown Prince's younger brother and his wife appeared with a son of their own, ensuring the safety of the succession.

As an American, I am kind of mystified and bemused at the idea of a monarch, and it seemed to me that most of the younger Japanese people I know are pretty apathetic about the whole issue, but I was curious what the older generation might think. After all, most of them lived when an Emperor still had power and apparently the institution still has meaning for them; it's always grandmas out in the crowd waving at the Emperor when he holds forth.

So for one of the topics, I asked them to talk about whether "Women should be allowed to become Emperor." I predicted an interesting talk about whether modern equality should trump traditions. I was very surprised however, as the debate they actually had quickly evolved into one over whether the Imperial system should continue at all - and most everyone said "No."

As it turns out, the Emperor currently receives a yearly stipend of several million dollars from the government. This, despite the fact that his role is entirely ornamental, and he is of course already quite wealthy due to extensive property holdings. Several women in the class were quite vehement in their displeasure of paying through taxes the salary of a man who "doesn't do anything" and yet lives in a huge complex completely isolated from the public. Others went even further, saying that the Imperial system itself is ridiculous and should be dismantled. The only dissenting opinion was the one man there that day, who said that the Emperor should be retained as a symbol of Japan. The women all disagreed though, saying they felt no connection for the Emperor, even as a symbol.

After the Japanese surrender, there was a debate among the American occupation forces about the future of the Imperial system. In the end, MacArthur and the Americans decided to keep the institution, albeit stripping it of its powers. MacArthur also refused calls to try the monarch for any responsibility in the war. He believed that any attempt to remove the Emperor would cause upheavals in Japan. Why? Because he, along with other Japan "experts", thought the people here were fundamentally incapable of thinking for themselves, and they could not have democracy here without the imperial system. They bought into the propaganda of the wartime government of Japan of the people as blindly obedient to the Emperor, and also believed in the myth of all the yellow people in general as ant-like followers.

In the end, it seems this was another example of taking the public front of a government for the feelings of all its citizens. The government talks about the respect and love people had for the Emperor, and I simply assumed that they believed exactly what the government said. I found that I still harbored some of the same patronizing views of people here as Americans did in the past.

Monday, October 09, 2006

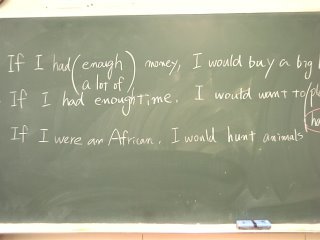

If I were an African, I'd smack that kid

On Friday I was teaching a second-year writing class with another teacher on the subjunctive mood (ex: if I were you, I would...). The writing class is filled with kids who, rather than simply providing simple answers, try their best to come up with something amusing and unexpected each time. To give you an idea of what it's like, both Duckboy and the sagely Life=Happiness Music kid are in the class.

On Friday I was teaching a second-year writing class with another teacher on the subjunctive mood (ex: if I were you, I would...). The writing class is filled with kids who, rather than simply providing simple answers, try their best to come up with something amusing and unexpected each time. To give you an idea of what it's like, both Duckboy and the sagely Life=Happiness Music kid are in the class.We're calling on students for example sentences using the subjunctive mood. The depressing answer of the day is the completion of the phrase, "If my father had more free time.." with "he could be working harder." Wow, sucks to be your dad, you little authoritarian prick. But generally, we get innocuous answers like "If I had enough money, I would buy a big house." and "If I had enough time, I would want to play soccer." Fair enough, I think.

Then the sage raises his hand and volunteers his sentence:

"If I were an African, I would hunt animals."

I go over to make sure that he actually wrote down what he just said.

Yeah, he did write and say that.

Meanwhile there is little response from the rest of the class, and as I turn around I realize the teacher has just gone ahead and written down his answer on the board. I roll my eyes and take this opportunity to teach the kid a couple of pertinent English words by leaning over to type into his electronic dictionary: "S-T-E-R-E-O-T-Y-P-E." and "I-G-N-O-R-A-N-T." as in, "If I were you, I'd be embarrassed as your stereotype shows how ignorant you are." I write this on the board and make a mental note to ask their social studies teacher to maybe point out next class that not all Africans are currently hunter-gatherers.

Later in class, I realize that they've all just copied down what I wrote on the board as if it was another example sentence from the textbook, missing the point entirely. JET internationalization fails again.

Sunday, October 08, 2006

Designated carpool

Last week we had the sports festival at school. Last year, I was excited to see all the kids out in their teams with their different colored shirts running around. This year, I stayed inside and read so I wouldn't get sunburned. Some things get old quickly.

It's quite a big event though; all of the students at the school have to participate in some capacity, and it goes on for the entire school day. The P.E. teachers have to plan and run the whole thing, so after a long day of work, they do what people do in Japanese workplaces everywhere - go out and get drunk. And I don't mean "a few beers with the boys" drunk, I mean "passing out in your suit on a bench in the train station" drunk.

The next morning, after getting out the shower I notice I got a call from my neighbor, one of the aforementioned teachers. I'm surprised because - though I often call him when it rains to get a ride to school - he has never once phoned me. I call him back.

Me: Good morning!

Teacher: RUKAS~! (He seems to really love yelling my name like this) Good morning.

Me: You called me?

Teacher: Ah...yes. I was going to ask you, can you drive a car?

Me: Huh? Yeah...Why?

Teacher: So, last night, after sports day, I had a drinking party with the other P.E. teachers...

Me: Ah, good work on sports day.

Teacher: Thanks...well, I had a bit too much to drink last night.

Me: Well, are you okay?

Teacher: Yes, but I'm still a little drunk, actually.

Me: (Pause) Umm, okay...

Teacher: So, would you mind driving me to school in my car?

Me: (Pause to laugh really hard)...Sure, no problem.

So, I go down and he's sitting in the passenger seat of his car with the car running, waiting for me. I jump in and we head off to school. He tells me he got home really late the night before after too many beers, and decided it wouldn't be safe for him to drive himself to work. On one level, I think this is responsible and admirable, as drunk driving is alarmingly commonplace - both in frequency and level of acceptance - in Japan. Of course, on another level, he is going to work drunk. And on another, more hilariously terrible level, he is going to teach at a school drunk!

I laugh about this the entire trip, even more as he keeps giving me directions on how to get there; I feign surprise and gratitude when he tells me where to turn to get into the parking lot. Sure, it's ridiculous, but I'm thinking about this too much as an American. There, this kind of thing would be considered alcoholism and could get you fired. Here, they hold drinking parties at least twice a term which all teachers are required to attend - and the hundreds of bottles of Kirin there are all paid for by the school.

In the end, I just laughed and told him to just stand out on the field during class with his sunglasses on and his arms crossed till he sobered up. After all, he's just a P.E. teacher; that's basically all he does every day anyway.

It's quite a big event though; all of the students at the school have to participate in some capacity, and it goes on for the entire school day. The P.E. teachers have to plan and run the whole thing, so after a long day of work, they do what people do in Japanese workplaces everywhere - go out and get drunk. And I don't mean "a few beers with the boys" drunk, I mean "passing out in your suit on a bench in the train station" drunk.

The next morning, after getting out the shower I notice I got a call from my neighbor, one of the aforementioned teachers. I'm surprised because - though I often call him when it rains to get a ride to school - he has never once phoned me. I call him back.

Me: Good morning!

Teacher: RUKAS~! (He seems to really love yelling my name like this) Good morning.

Me: You called me?

Teacher: Ah...yes. I was going to ask you, can you drive a car?

Me: Huh? Yeah...Why?

Teacher: So, last night, after sports day, I had a drinking party with the other P.E. teachers...

Me: Ah, good work on sports day.

Teacher: Thanks...well, I had a bit too much to drink last night.

Me: Well, are you okay?

Teacher: Yes, but I'm still a little drunk, actually.

Me: (Pause) Umm, okay...

Teacher: So, would you mind driving me to school in my car?

Me: (Pause to laugh really hard)...Sure, no problem.

So, I go down and he's sitting in the passenger seat of his car with the car running, waiting for me. I jump in and we head off to school. He tells me he got home really late the night before after too many beers, and decided it wouldn't be safe for him to drive himself to work. On one level, I think this is responsible and admirable, as drunk driving is alarmingly commonplace - both in frequency and level of acceptance - in Japan. Of course, on another level, he is going to work drunk. And on another, more hilariously terrible level, he is going to teach at a school drunk!

I laugh about this the entire trip, even more as he keeps giving me directions on how to get there; I feign surprise and gratitude when he tells me where to turn to get into the parking lot. Sure, it's ridiculous, but I'm thinking about this too much as an American. There, this kind of thing would be considered alcoholism and could get you fired. Here, they hold drinking parties at least twice a term which all teachers are required to attend - and the hundreds of bottles of Kirin there are all paid for by the school.

In the end, I just laughed and told him to just stand out on the field during class with his sunglasses on and his arms crossed till he sobered up. After all, he's just a P.E. teacher; that's basically all he does every day anyway.

Monday, October 02, 2006

Everything true and real

The beginning of the school year here means another 400 speeches for me to attempt to correct. When fortune smiles upon me, I just have countless speeches about club activities with simple grammatical and spelling mistakes to make it through. These depress me terribly, because they prove how terribly depressing most of the kids' lives are - even during summer they spend too much time studying and doing club activities and don't see their friends - but at least I can slog through them. Sometimes I am hit by a paper that is basically indecipherable; it looks like it has been translated word for word from Japanese to English, despite the complete lack of structural affinity of the two languages; it contains bizarre sentences without subjects or objects that I cannot conceive of; it is still written partly in Japanese that I have to then translate. These take much longer to get through, because they often seem to have been penned by Gollum, all sentences with off-putting subjects ("It tires," "It hurts us", "It eats well,") possessing that same structure of a maniacal rant struck down on paper.

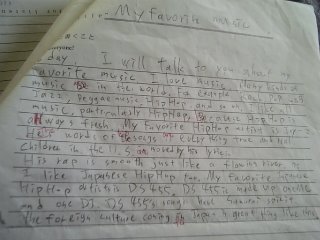

The beginning of the school year here means another 400 speeches for me to attempt to correct. When fortune smiles upon me, I just have countless speeches about club activities with simple grammatical and spelling mistakes to make it through. These depress me terribly, because they prove how terribly depressing most of the kids' lives are - even during summer they spend too much time studying and doing club activities and don't see their friends - but at least I can slog through them. Sometimes I am hit by a paper that is basically indecipherable; it looks like it has been translated word for word from Japanese to English, despite the complete lack of structural affinity of the two languages; it contains bizarre sentences without subjects or objects that I cannot conceive of; it is still written partly in Japanese that I have to then translate. These take much longer to get through, because they often seem to have been penned by Gollum, all sentences with off-putting subjects ("It tires," "It hurts us", "It eats well,") possessing that same structure of a maniacal rant struck down on paper.Then there are the fantastic ones like this (Please click on the picture and read). He begins talking about how he loves music, which I appreciate, and then starts talking about how his favorite kind of music is hip-hop. Any kid who doesn't listen to Japanese Pop is cool to me, but then he ups the ante by dropping the name of Jay-Z. The rest of the essay is just pure gold. This is my favorite type of writing I get from students, because it is simply non-reproducible by a native speaker. Freed from an understanding of diction, style, and often grammar itself, and the burdens those things may impose, the Japanese students seem to be able to do things unintentionally with English that are both hilarious and novel.

There are some great lines: "His rap is smooth just like a flowing river," and the songs "have the samurai spirit." But, my favorite part has to be when he writes, "the words of [his] songs [are] everything true and real."

I believe what he meant is, "Everything Jay-Z says in his songs is true and real." But, instead of that stolid phrase, he says the words themselves are everything true and real. He's not talking about the veracity of Jay-Z's experiences, but claiming that the words of Jay-Z represent, perhaps even create, truth and reality in themselves! What made me laugh even more than this, was that it almost sounded like something Jay-Z himself would say; it's the kind of self-aggrandizing lyric a rapper would wish he'd written.

Long story short, I gave this guy high marks and told him I expected a report on the meaning of the song "Girls, Girls, Girls" next week.

Saturday, September 16, 2006

Breaking old promises

School just started again after the summer break, and I'm getting back into the grind of waking up too early and dragging myself in to dance around for my little English lesson/minstrel show for the students. It being the second year, I'm using the same lessons from last year, so I've got the routine down pat. Like last year, I'm preparing students for a speech contest (more on that later) and grading almost 400 speeches others were required to write for English class.

School just started again after the summer break, and I'm getting back into the grind of waking up too early and dragging myself in to dance around for my little English lesson/minstrel show for the students. It being the second year, I'm using the same lessons from last year, so I've got the routine down pat. Like last year, I'm preparing students for a speech contest (more on that later) and grading almost 400 speeches others were required to write for English class.And so I was in a Starbucks in the city grading these tests when a girl walked up to me and started waving. Lots of students walk or bike by me waving whenever I'm in the city, but, raising my eyes with some suspicion and giving her the quick once-over, I saw that she wasn't wearing a school uniform. This seemed to place her in that dubious category of Japanese that might just wave at me, a complete stranger, just for being tall, white, and red-crested. My interest in Japanese just for their Japanese-ness currently being nil, I decided to ignore her and went back to grading.

But, she as she ran up and yelled, "Mr. Adams!" at me, still waving, I looked closer and saw Mami, the girl I tutored last year for entrance interviews for her university. You know, the one the Vice Principal wanted me to promise not to make fall in love with me. In the end, she passed the interview, was accepted, and went off to Nanzan University in Nagoya to study English. This was the first time I'd talked to her since graduation, so it was really nice to see her. She looked very different outside of school - namely, not in a uniform. I'd say she looked older as well, but that has to be taken relatively, in the sense that most all of the students look like they're 14 anyway so it wouldn't take much to build on that. She and 3 of her friends sat down with me and chatted for a while about their college lives.

Being a bit depressed at teaching the same lame lessons and grading the same boring speeches about club activities, seeing her was exactly what I needed: a reminder of the impact I can have on kid's lives. Not in some vague way about changing their perceptions of foreigners, opening their minds to the wonders of English, or whatever; no, in the definite sense that I got that girl into college. And she's going to remember that, and with something so small I was able to change someone else's life. So the minstrel show will go on, because I've got one more year to get to the rest of those kids.

After talking to her for a while though, it became clear that she's remembering me for other reasons too. Looks like I broke my promise to the Vice Principal after all...

Tuesday, July 18, 2006

Speaking of hostess clubs

A couple times a month I teach an English conversation class on Saturday at the local community center to a small group of mostly elderly students. They're all really nice, aside from being much more motivated and easier to teach than the high school kids I deal with generally.

Since I live a bit away, they take turns each time picking me up to bring me to the center. Last class one of the women from the class came to pick me up and as we drove we chatted a bit. It was a little hard going because though she is basically the worst student in the class, she doesn't want me to speak Japanese. Basically, all the students seem to take any time outside of class with me as a free English lesson, so they're always trying to wring every use out of me possible.

We're talking a bit about my plans for the weekend as we pull into the parking lot. Just as I move to take off my seatbelt though, she taps me on the shoulder and a card suddenly materializes into her hand. I look down and find myself holding a business card from "Pleasure Square" for a certain Rena.

"What's this?" I ask

Her: "A card."

Me: "Who's Rena?"

Her: "Ah...my daughter."

Me: "Wait, wait, your daughter is a hostess!?"

Her: "No, she's not. It's a part-time job."

Me: "Yeah, so she's a hostess part-time."

Her: (Sighs)

Me: "Why are you giving this to me?"

Her: "Well...you should go."

Me: "Umm...sorry, but hostess bars are too expensive for me."

Her: "Yes, weekends are expensive but if you go on Monday it is only 3000 yen."

Me: "I don't know..."

Her: "Go. I told her about you. You'd like her."

And then I got out and taught the class. What was so amusing to me was how she was both embarrassed at her daughter's job but simultaneously trying to drum up more business for her. Unfortunately, aside from the fact that I would not pay anyone for a conversation, looking at this woman, to be bitterly honest, I would especially not pay to talk to her daughter.

Since I live a bit away, they take turns each time picking me up to bring me to the center. Last class one of the women from the class came to pick me up and as we drove we chatted a bit. It was a little hard going because though she is basically the worst student in the class, she doesn't want me to speak Japanese. Basically, all the students seem to take any time outside of class with me as a free English lesson, so they're always trying to wring every use out of me possible.

We're talking a bit about my plans for the weekend as we pull into the parking lot. Just as I move to take off my seatbelt though, she taps me on the shoulder and a card suddenly materializes into her hand. I look down and find myself holding a business card from "Pleasure Square" for a certain Rena.

"What's this?" I ask

Her: "A card."

Me: "Who's Rena?"

Her: "Ah...my daughter."

Me: "Wait, wait, your daughter is a hostess!?"

Her: "No, she's not. It's a part-time job."

Me: "Yeah, so she's a hostess part-time."

Her: (Sighs)

Me: "Why are you giving this to me?"

Her: "Well...you should go."

Me: "Umm...sorry, but hostess bars are too expensive for me."

Her: "Yes, weekends are expensive but if you go on Monday it is only 3000 yen."

Me: "I don't know..."

Her: "Go. I told her about you. You'd like her."

And then I got out and taught the class. What was so amusing to me was how she was both embarrassed at her daughter's job but simultaneously trying to drum up more business for her. Unfortunately, aside from the fact that I would not pay anyone for a conversation, looking at this woman, to be bitterly honest, I would especially not pay to talk to her daughter.

Thursday, June 22, 2006

The "Sublime" of English

I went to Tokyo for a dreadful re-contracting conference - rife with all the inanity and frustration typical of the bureaucratic JET Program conferences and events - and then we had our school festival shortly afterwards. The school festival is a yearly event in which the all the students participate, both through their homerooms and in their club activities. Each homeroom or club is given a classroom or booth and decides on a theme and some activity. The theme of this year's festival was "The Sublime."

I went to Tokyo for a dreadful re-contracting conference - rife with all the inanity and frustration typical of the bureaucratic JET Program conferences and events - and then we had our school festival shortly afterwards. The school festival is a yearly event in which the all the students participate, both through their homerooms and in their club activities. Each homeroom or club is given a classroom or booth and decides on a theme and some activity. The theme of this year's festival was "The Sublime." The English club was to translate the program for the festival into English. The program contained little descriptions written by students of what each club or homeroom was doing in their area. This simple translation taks became a chore since even in Japanese none of what the kids had written in the program made sense, and it was further complicated by the fact that most every sentence describing the different activities at the festival used the word "Sublime," rendering the entire thing nonsensical.

Some selections:

Some selections:24HR "Sublime" Chocolate Bananas: Come taste the "sublime" in bananas!

(The two girls in the picture are advertising their bananas)

Calligraphy club: Has the calligraphy club reached the "sublime" of writing? The answer is...Takashi!

28HR Entrance of a large hall: Tokyo Friend Park! Enter the unknown world inhabited by a mysterious maid

30HR No Goblin!: Throw off your stress and destroy the goblins!

(and my favorite)

39HR Men's Paradise: A world-class paradise for men. We invite you to this world of both fear and laughter

As the program clearly completely fails to convey any idea of what one might find at the booths, the second year students in the English club were also to conduct tours of the festival in English for any foreign visitors. So they would have someone to actually give a tour to on the day, it fell upon me and my well-known contacts in the foreigner community to provide these foreigners who speak English. I brought Matt.

When he arrived, all the girls were busy so we had KMK - I believe I touted his greatness in a previous blog post - give us a solo tour. He took us around and gesticulated wildly at various exhibits.

Here is KMK and his harem. KMK actually has a girlfriend in the second year, but since I don't think she's good enough for him, Matt and I kept needling him about going after this first year girl on the right. As the girls here were in the cooking club, Matt played up that angle, while I convinced KMK that this girl had an elegant, rare "old Japan"- type of beauty. He went red and gesticulated in an even wilder fashion - if that can be believed.

Here is KMK and his harem. KMK actually has a girlfriend in the second year, but since I don't think she's good enough for him, Matt and I kept needling him about going after this first year girl on the right. As the girls here were in the cooking club, Matt played up that angle, while I convinced KMK that this girl had an elegant, rare "old Japan"- type of beauty. He went red and gesticulated in an even wilder fashion - if that can be believed.Matt and I also enjoyed going to the biology club's exhibit, where a series of tanks housed various interesting fish and aquatic animals. After listening to the explanation given by the biology club students at each station, we would conduct this dialogue:

Student: This is a very rare fish.

Student: This is a very rare fish.Me: Hmm...that's very interesting. But let me ask this though, can we eat that fish, now?

Student: Oh oh! No no no no!

Matt: But I'm hungry (rubs stomach) and I want to eat the fish. C'mon buddy.

Student: No no no, I-we-ah ah, need the fish!

Me: Ah, okay okay, I totally understand. You can't give us the fish because you need them for the festival, right?

Student: (Visibly relieved) Yes, yes.

Matt: How about this then, we come back in a couple hours, when you close, and then we eat the fish?

Student: Oh oh no! (waving arms frantically as I reach my hand towards the tank)

We ran through this routine at every tank. Then we took turns distracting the students while we took pictures with our hands in the piranha tank. KMK was going into convulsions at this point.

We ended up back at the English club's room, where we had set up English karaoke. My laptop was hooked up to a TV and a stereo, playing music videos from a list of songs. The idea was that the first year kids would look up the lyrics for the songs on the internet and put together a booklet of English lyrics for visitors to our room to use. As it turns out though, none of the students were at all capable of doing anything with a computer, even typing the name of a song into Google, so in the end I had to set up the entire thing myself. The room also shut down for large amounts of the day as they would click on the wrong box and had to chase me down to fix the computer. This seemed to be pretty much par for the course though, with all the teachers involved in their homerooms and clubs doing enormously disproportionate amounts of work for something ostensibly to be run entirely by the students for the students.

We ended up back at the English club's room, where we had set up English karaoke. My laptop was hooked up to a TV and a stereo, playing music videos from a list of songs. The idea was that the first year kids would look up the lyrics for the songs on the internet and put together a booklet of English lyrics for visitors to our room to use. As it turns out though, none of the students were at all capable of doing anything with a computer, even typing the name of a song into Google, so in the end I had to set up the entire thing myself. The room also shut down for large amounts of the day as they would click on the wrong box and had to chase me down to fix the computer. This seemed to be pretty much par for the course though, with all the teachers involved in their homerooms and clubs doing enormously disproportionate amounts of work for something ostensibly to be run entirely by the students for the students.  Anyhow, our club event proved less than popular that day, so I also did a disproportionate amount of the singing - though I was less frustrated by that outcome - since even the kids in the club most enthusiastic about the karaoke balked about actually singing in front of others once the time came. In between bouts of my crooning though, KMK stepped up and delivered a surprisingly manly rendition of that O-Zone song, "Dragostea Din Tei"...And no one was left unmoved! I tried to counter by singing A-ha "Take on Me" as a duet with this quiet third-year kid (God knows why he knew all the lyrics), but we just couldn't match KMK's visceral power. It didn't help that my partner for the duet looked like a janitor in his outfit.

Anyhow, our club event proved less than popular that day, so I also did a disproportionate amount of the singing - though I was less frustrated by that outcome - since even the kids in the club most enthusiastic about the karaoke balked about actually singing in front of others once the time came. In between bouts of my crooning though, KMK stepped up and delivered a surprisingly manly rendition of that O-Zone song, "Dragostea Din Tei"...And no one was left unmoved! I tried to counter by singing A-ha "Take on Me" as a duet with this quiet third-year kid (God knows why he knew all the lyrics), but we just couldn't match KMK's visceral power. It didn't help that my partner for the duet looked like a janitor in his outfit. Most all of the kids were wearing their t-shirts for their respective homerooms, and those not in the shirts were all wearing costumes of a sort. The girls in the tea ceremony club wore yukata or kimono, the girls running the host club (more on that later) wore flashy dress shirts and skirts, others wore flowers in their hair.

Most all of the kids were wearing their t-shirts for their respective homerooms, and those not in the shirts were all wearing costumes of a sort. The girls in the tea ceremony club wore yukata or kimono, the girls running the host club (more on that later) wore flashy dress shirts and skirts, others wore flowers in their hair.While the girls seemed to be dressed up in adorable, graceful or (for school) almost indecent clothes, the boys had taken the occasion to voluntarily serve up their pride to the utmost derision, by me and Matt, at least.

Here is a prime suspect; a 17 year old guy wearing a monkey suit I assume he bought at some store selling little boy's Halloween costumes. Not only was he prancing around in the suit, but he also stopped to pose for this picture with Matt holding onto his tail. I suppose it could be fun for some to see kids taking themselves so lightly, but everyone should have their limits.

Here is a prime suspect; a 17 year old guy wearing a monkey suit I assume he bought at some store selling little boy's Halloween costumes. Not only was he prancing around in the suit, but he also stopped to pose for this picture with Matt holding onto his tail. I suppose it could be fun for some to see kids taking themselves so lightly, but everyone should have their limits. Though fortunately I don't have any pictures of this, there were also a disturbingly high number of boys dressed in drag of one kind or another. I suppose their lack of body hair and general possession of the physique of a prepubescent girl makes them particularly fit for this role, but I still found it rather baffling, aside from just unsettling. Boys wearing kimono, boys wearing girl's school uniforms, boys in tennis skirts, and - by far the most nauseating - a boy in a slit China dress. Ugh... (He danced up to me and asked, "Cute? Cute?" "No," I replied most emphatically, "Just disgusting.") Sorry dude, cross-dressing does not equal instant hilarity.

Though fortunately I don't have any pictures of this, there were also a disturbingly high number of boys dressed in drag of one kind or another. I suppose their lack of body hair and general possession of the physique of a prepubescent girl makes them particularly fit for this role, but I still found it rather baffling, aside from just unsettling. Boys wearing kimono, boys wearing girl's school uniforms, boys in tennis skirts, and - by far the most nauseating - a boy in a slit China dress. Ugh... (He danced up to me and asked, "Cute? Cute?" "No," I replied most emphatically, "Just disgusting.") Sorry dude, cross-dressing does not equal instant hilarity. Later, I further fulfilled my bond by bringing a few more friends to get an English tour when Kevin, Joyce, and Yukari showed up. KMK, now joined by his friend, proved himself no more a master of verbal and no less a master of non-verbal communication on his second tour. After a few rounds of karaoke, we stopped by the tea ceremony club to have tea and a snack, and beckoned in by the girls outside, then decided to check out the room that was running a host club.

Later, I further fulfilled my bond by bringing a few more friends to get an English tour when Kevin, Joyce, and Yukari showed up. KMK, now joined by his friend, proved himself no more a master of verbal and no less a master of non-verbal communication on his second tour. After a few rounds of karaoke, we stopped by the tea ceremony club to have tea and a snack, and beckoned in by the girls outside, then decided to check out the room that was running a host club. The fact that a host club had been allowed in the festival kind of confused me, since it seemed wildly inappropriate, even as a joke. Host or hostess clubs in Japan are bars where patrons pay to be waited on and surrounded by male or female hosts, respectively. Usually it's a place salarymen go after work to I guess pay to be fawned on and treated as the center of attention after a day of demeaning and humiliating servitude, though recently bars with young men catering to women are becoming popular as well.There is apparently nothing necessarily untoward about it - nothing is being bought except someone's company and time - but it still seems wildly inappropriate to field a mock one at the school festival. I've never gone to a hostess club because I have never had a conversation I would be willing to pay someone for. Let's just say the school's club didn't change my mind on that score.

The fact that a host club had been allowed in the festival kind of confused me, since it seemed wildly inappropriate, even as a joke. Host or hostess clubs in Japan are bars where patrons pay to be waited on and surrounded by male or female hosts, respectively. Usually it's a place salarymen go after work to I guess pay to be fawned on and treated as the center of attention after a day of demeaning and humiliating servitude, though recently bars with young men catering to women are becoming popular as well.There is apparently nothing necessarily untoward about it - nothing is being bought except someone's company and time - but it still seems wildly inappropriate to field a mock one at the school festival. I've never gone to a hostess club because I have never had a conversation I would be willing to pay someone for. Let's just say the school's club didn't change my mind on that score.

Tuesday, June 20, 2006

The Beer Festival

Matt came for another visit on the 25th, just leaving last week on the 13th. By the end, I was tired as hell and sick to boot. Now I think I can write a little about it, weekend by weekend.

I had already decided on our plan for that first weekend more than a month prior, when while reading the Daily Yomiuiri newspaper I found an article about the Japan Beer Festival. Over 100 Japanese microbrews? We were there before Matt had even finalized his plane ticket.

I had already decided on our plan for that first weekend more than a month prior, when while reading the Daily Yomiuiri newspaper I found an article about the Japan Beer Festival. Over 100 Japanese microbrews? We were there before Matt had even finalized his plane ticket.

So we went to Osaka for the festival and paid 3,000 yen for a 4 hour nomihodai (all you can drink) of more than 100 Japanese craft beers. They tried to handicap us a bit by only providing a 60mL cup, but that proved a futile gesture. Within the first half-hour, we had already sampled all of the beers. By the end of the first hour, we had decided on our favorite brew and taken up permanent residence at their table. By the second hour, Matt had installed himself behind the counter of the brewery booth - despite the continued protests of the woman distributing the samples - and we made a vow to this boisterous Kansai woman that we would drink all of her sample bottles ourselves.

Kansai people - that is, those from the Kansai region of the main island that encompasses Kyoto, Osaka and Kobe - deserve their reputation as a fiery lot though, as you can see in the next picture. As they finally closed the show down and forced us out, we stumbled out with a few souvenir bottles and our skateboards. I think we were able to skate about 10 feet in a looping, parabolic shape before tumbling to the ground. Matt also managed the impressive feat of forgetting he had put this glass bottle in his back pocket, and cut his hand open right good. This would prove to be only the first of many, many falls. Eventually, after we patched him up, we headed off into the city.

Kansai people - that is, those from the Kansai region of the main island that encompasses Kyoto, Osaka and Kobe - deserve their reputation as a fiery lot though, as you can see in the next picture. As they finally closed the show down and forced us out, we stumbled out with a few souvenir bottles and our skateboards. I think we were able to skate about 10 feet in a looping, parabolic shape before tumbling to the ground. Matt also managed the impressive feat of forgetting he had put this glass bottle in his back pocket, and cut his hand open right good. This would prove to be only the first of many, many falls. Eventually, after we patched him up, we headed off into the city.

We skated around the bright lights of Osaka, dodging frightened old women and chatting up various impressed locals. Later we went out for sushi at one of those restaurants with revolving belts, and, though I only vaguely remember this, I believe got kicked out after we started chucking pieces of tuna against the walls to see if they would stick. I guess it was just that kind of night. Eventually we made it back to a hotel.

The next morning we awoke to find ourselves covered quite evenly with bruises and scrapes. Matt's hand was killing him and I had a nice imprint of a button from my jeans etched into my hip like a head of branded cattle. Pulling it together, we eventually set off to see Himeji, the most impressive castle in Japan. A World Heritage Site, it did not disappoint, to be sure; a massive complex but with a rugged beauty and white exterior that lends it the nickname, the "white heron" castle.

The next morning we awoke to find ourselves covered quite evenly with bruises and scrapes. Matt's hand was killing him and I had a nice imprint of a button from my jeans etched into my hip like a head of branded cattle. Pulling it together, we eventually set off to see Himeji, the most impressive castle in Japan. A World Heritage Site, it did not disappoint, to be sure; a massive complex but with a rugged beauty and white exterior that lends it the nickname, the "white heron" castle.

The castle is also known for the maze-like path that leads to the main keep. The path circles around in a spiral with many dead ends, leaving any potential attackers open to constant attack from the surrounding walls. Himeji was never actually attacked however, so this design remains untested. I should say, "had never" been attacked, because Matt and I took it upon ourselves to take up the task it seems lesser men wilted at.

The castle is also known for the maze-like path that leads to the main keep. The path circles around in a spiral with many dead ends, leaving any potential attackers open to constant attack from the surrounding walls. Himeji was never actually attacked however, so this design remains untested. I should say, "had never" been attacked, because Matt and I took it upon ourselves to take up the task it seems lesser men wilted at.  Fortunately, this sign's improper use of indefinite articles (climbing "a" wall is prohibited, sure, but how are we to know which wall? It could be any wall, anywhere, right?) left us able to climb without fear of reprisal, as well. I think a young Japanese boy said it best who, after spotting us, cried out "NINJA!" Unfortunately, there were no more samurai sentries left in the castle to come to his aid when I fell upon him like cold, black night, cutting his scream off abruptly with a jab to the windpipe. When in Rome, you know?

Fortunately, this sign's improper use of indefinite articles (climbing "a" wall is prohibited, sure, but how are we to know which wall? It could be any wall, anywhere, right?) left us able to climb without fear of reprisal, as well. I think a young Japanese boy said it best who, after spotting us, cried out "NINJA!" Unfortunately, there were no more samurai sentries left in the castle to come to his aid when I fell upon him like cold, black night, cutting his scream off abruptly with a jab to the windpipe. When in Rome, you know?

We climbed several flights of steep stairs, pushing aside Japanese women, children, and the elderly in our wake as we made our ascent to the top. I fell prey to one of the other hidden defenses of the castle when I cracked my skull repeatedly on the low hanging doorways throughout the building. I definitely would not be the ideal person to storm a castle in which I would have to stoop down the entire time, leaving my neck generously extended for anyone who happened to have a really sharp sword or two in hand. As always seems to happen when I travel in Japan, I was embarrassed to be tired at the end when I saw how many old women past 70 had made the trek seemingly unfazed.

We climbed several flights of steep stairs, pushing aside Japanese women, children, and the elderly in our wake as we made our ascent to the top. I fell prey to one of the other hidden defenses of the castle when I cracked my skull repeatedly on the low hanging doorways throughout the building. I definitely would not be the ideal person to storm a castle in which I would have to stoop down the entire time, leaving my neck generously extended for anyone who happened to have a really sharp sword or two in hand. As always seems to happen when I travel in Japan, I was embarrassed to be tired at the end when I saw how many old women past 70 had made the trek seemingly unfazed.

Later that afternoon we dropped in at Kobe - a charming city - and were, as you see here, greeted by many an adoring female admirer. We skated around, soaked up the local color, watched a terrible street band perform, and ate the local specialty, okonomiyaki, which is kind of a pancake with cabbage. We hopped a train back to Hamamatsu that night and laughed at how we had been in three major cities in that one day. In a reoccuring pattern for the trip, I arrived at work the next morning exhausted while Matt went off exploring somewhere else fun. He was, however, always kind enough to call me in between classes to tell me about all the fun places he was visiting. Thanks, buddy.

Later that afternoon we dropped in at Kobe - a charming city - and were, as you see here, greeted by many an adoring female admirer. We skated around, soaked up the local color, watched a terrible street band perform, and ate the local specialty, okonomiyaki, which is kind of a pancake with cabbage. We hopped a train back to Hamamatsu that night and laughed at how we had been in three major cities in that one day. In a reoccuring pattern for the trip, I arrived at work the next morning exhausted while Matt went off exploring somewhere else fun. He was, however, always kind enough to call me in between classes to tell me about all the fun places he was visiting. Thanks, buddy.

I had already decided on our plan for that first weekend more than a month prior, when while reading the Daily Yomiuiri newspaper I found an article about the Japan Beer Festival. Over 100 Japanese microbrews? We were there before Matt had even finalized his plane ticket.

I had already decided on our plan for that first weekend more than a month prior, when while reading the Daily Yomiuiri newspaper I found an article about the Japan Beer Festival. Over 100 Japanese microbrews? We were there before Matt had even finalized his plane ticket.So we went to Osaka for the festival and paid 3,000 yen for a 4 hour nomihodai (all you can drink) of more than 100 Japanese craft beers. They tried to handicap us a bit by only providing a 60mL cup, but that proved a futile gesture. Within the first half-hour, we had already sampled all of the beers. By the end of the first hour, we had decided on our favorite brew and taken up permanent residence at their table. By the second hour, Matt had installed himself behind the counter of the brewery booth - despite the continued protests of the woman distributing the samples - and we made a vow to this boisterous Kansai woman that we would drink all of her sample bottles ourselves.

Kansai people - that is, those from the Kansai region of the main island that encompasses Kyoto, Osaka and Kobe - deserve their reputation as a fiery lot though, as you can see in the next picture. As they finally closed the show down and forced us out, we stumbled out with a few souvenir bottles and our skateboards. I think we were able to skate about 10 feet in a looping, parabolic shape before tumbling to the ground. Matt also managed the impressive feat of forgetting he had put this glass bottle in his back pocket, and cut his hand open right good. This would prove to be only the first of many, many falls. Eventually, after we patched him up, we headed off into the city.

Kansai people - that is, those from the Kansai region of the main island that encompasses Kyoto, Osaka and Kobe - deserve their reputation as a fiery lot though, as you can see in the next picture. As they finally closed the show down and forced us out, we stumbled out with a few souvenir bottles and our skateboards. I think we were able to skate about 10 feet in a looping, parabolic shape before tumbling to the ground. Matt also managed the impressive feat of forgetting he had put this glass bottle in his back pocket, and cut his hand open right good. This would prove to be only the first of many, many falls. Eventually, after we patched him up, we headed off into the city.We skated around the bright lights of Osaka, dodging frightened old women and chatting up various impressed locals. Later we went out for sushi at one of those restaurants with revolving belts, and, though I only vaguely remember this, I believe got kicked out after we started chucking pieces of tuna against the walls to see if they would stick. I guess it was just that kind of night. Eventually we made it back to a hotel.

The next morning we awoke to find ourselves covered quite evenly with bruises and scrapes. Matt's hand was killing him and I had a nice imprint of a button from my jeans etched into my hip like a head of branded cattle. Pulling it together, we eventually set off to see Himeji, the most impressive castle in Japan. A World Heritage Site, it did not disappoint, to be sure; a massive complex but with a rugged beauty and white exterior that lends it the nickname, the "white heron" castle.

The next morning we awoke to find ourselves covered quite evenly with bruises and scrapes. Matt's hand was killing him and I had a nice imprint of a button from my jeans etched into my hip like a head of branded cattle. Pulling it together, we eventually set off to see Himeji, the most impressive castle in Japan. A World Heritage Site, it did not disappoint, to be sure; a massive complex but with a rugged beauty and white exterior that lends it the nickname, the "white heron" castle.  The castle is also known for the maze-like path that leads to the main keep. The path circles around in a spiral with many dead ends, leaving any potential attackers open to constant attack from the surrounding walls. Himeji was never actually attacked however, so this design remains untested. I should say, "had never" been attacked, because Matt and I took it upon ourselves to take up the task it seems lesser men wilted at.

The castle is also known for the maze-like path that leads to the main keep. The path circles around in a spiral with many dead ends, leaving any potential attackers open to constant attack from the surrounding walls. Himeji was never actually attacked however, so this design remains untested. I should say, "had never" been attacked, because Matt and I took it upon ourselves to take up the task it seems lesser men wilted at.  Fortunately, this sign's improper use of indefinite articles (climbing "a" wall is prohibited, sure, but how are we to know which wall? It could be any wall, anywhere, right?) left us able to climb without fear of reprisal, as well. I think a young Japanese boy said it best who, after spotting us, cried out "NINJA!" Unfortunately, there were no more samurai sentries left in the castle to come to his aid when I fell upon him like cold, black night, cutting his scream off abruptly with a jab to the windpipe. When in Rome, you know?

Fortunately, this sign's improper use of indefinite articles (climbing "a" wall is prohibited, sure, but how are we to know which wall? It could be any wall, anywhere, right?) left us able to climb without fear of reprisal, as well. I think a young Japanese boy said it best who, after spotting us, cried out "NINJA!" Unfortunately, there were no more samurai sentries left in the castle to come to his aid when I fell upon him like cold, black night, cutting his scream off abruptly with a jab to the windpipe. When in Rome, you know? We climbed several flights of steep stairs, pushing aside Japanese women, children, and the elderly in our wake as we made our ascent to the top. I fell prey to one of the other hidden defenses of the castle when I cracked my skull repeatedly on the low hanging doorways throughout the building. I definitely would not be the ideal person to storm a castle in which I would have to stoop down the entire time, leaving my neck generously extended for anyone who happened to have a really sharp sword or two in hand. As always seems to happen when I travel in Japan, I was embarrassed to be tired at the end when I saw how many old women past 70 had made the trek seemingly unfazed.

We climbed several flights of steep stairs, pushing aside Japanese women, children, and the elderly in our wake as we made our ascent to the top. I fell prey to one of the other hidden defenses of the castle when I cracked my skull repeatedly on the low hanging doorways throughout the building. I definitely would not be the ideal person to storm a castle in which I would have to stoop down the entire time, leaving my neck generously extended for anyone who happened to have a really sharp sword or two in hand. As always seems to happen when I travel in Japan, I was embarrassed to be tired at the end when I saw how many old women past 70 had made the trek seemingly unfazed. Later that afternoon we dropped in at Kobe - a charming city - and were, as you see here, greeted by many an adoring female admirer. We skated around, soaked up the local color, watched a terrible street band perform, and ate the local specialty, okonomiyaki, which is kind of a pancake with cabbage. We hopped a train back to Hamamatsu that night and laughed at how we had been in three major cities in that one day. In a reoccuring pattern for the trip, I arrived at work the next morning exhausted while Matt went off exploring somewhere else fun. He was, however, always kind enough to call me in between classes to tell me about all the fun places he was visiting. Thanks, buddy.

Later that afternoon we dropped in at Kobe - a charming city - and were, as you see here, greeted by many an adoring female admirer. We skated around, soaked up the local color, watched a terrible street band perform, and ate the local specialty, okonomiyaki, which is kind of a pancake with cabbage. We hopped a train back to Hamamatsu that night and laughed at how we had been in three major cities in that one day. In a reoccuring pattern for the trip, I arrived at work the next morning exhausted while Matt went off exploring somewhere else fun. He was, however, always kind enough to call me in between classes to tell me about all the fun places he was visiting. Thanks, buddy.

Sunday, June 18, 2006

The School "Excursion"

For several weeks previous, anticipation had been building for our "school excursion", to which I was invited along. For some reason, this is the English translation of the word ensoku that apparently every Japanese learns in English class. Hearing teachers talk about this excursion business made me rather excited about what we might do. However, it seems that rather than "excursion" - which conjures up images of some voyage into jungle primeval, trek across the frozen tundra of the Far North, or perilous attempt at the summit of some great slag of rock - it turns out it would be much more accurate to render the word as "field trip", with all the banality that term usually conveys.

For several weeks previous, anticipation had been building for our "school excursion", to which I was invited along. For some reason, this is the English translation of the word ensoku that apparently every Japanese learns in English class. Hearing teachers talk about this excursion business made me rather excited about what we might do. However, it seems that rather than "excursion" - which conjures up images of some voyage into jungle primeval, trek across the frozen tundra of the Far North, or perilous attempt at the summit of some great slag of rock - it turns out it would be much more accurate to render the word as "field trip", with all the banality that term usually conveys.For banal our field trip was. All students in all homerooms of all three grade levels were loaded off into buses in the morning, each grade bound for a different exciting location, one homeroom per chartered bus. Since I'm teaching first-year students mostly, I opted to go along with the intrepid explorers of 14 HR. Due to rain that morning, a trip to a historic village and hiking was called off in favor of a visit to the Toyota Museum. I thought it might still be fun though, since some of the greatest art to be seen in Japan is owned by various corporations.

A 2-hour bus ride later, I discovered that this was not, as I had assumed, a museum of art owned by the Toyota corporation, but in fact a museum of Toyota cars. As in, a car museum. As in, a museum about the history of the automobile. As in, line after line of cars with placards in front of them. Kind of like going on a field trip to the exotic "Mile of Cars."

Look at the expression on the girl's face in the front in this picture. That's how we all felt. Upon our entrance, we were given about an hour to walk around and enjoy the exhibits. I finished my cursory walk around with some students in about 5 minutes. I gave a personal tour to the kids with commentary: "And here on your right, you will see...another car. And if you walk a little farther, coming up on your left is...this other car. Ah, now we've come to my favorite part of the entire tour - the part where we can all look at this car. Isn't this a particularly fascinating car?" Then I pretended to take an exhaustive series of pictures of the car in question. The tour was over in 5 minutes because I couldn't even amuse myself for that long, and I find myself quite amusing usually. I still can't believe we went to a car museum, but I guess it's hard to find a place to just throw a couple hundred kids in for hours at a time.

Look at the expression on the girl's face in the front in this picture. That's how we all felt. Upon our entrance, we were given about an hour to walk around and enjoy the exhibits. I finished my cursory walk around with some students in about 5 minutes. I gave a personal tour to the kids with commentary: "And here on your right, you will see...another car. And if you walk a little farther, coming up on your left is...this other car. Ah, now we've come to my favorite part of the entire tour - the part where we can all look at this car. Isn't this a particularly fascinating car?" Then I pretended to take an exhaustive series of pictures of the car in question. The tour was over in 5 minutes because I couldn't even amuse myself for that long, and I find myself quite amusing usually. I still can't believe we went to a car museum, but I guess it's hard to find a place to just throw a couple hundred kids in for hours at a time. After a long lunch, we still had too much time leftover to just go back to school, so we headed to Nagoya to see Nagoya Castle. One teacher, noting my disappointed look leftover from the last stop, tried to buoy my spirits a little by talking up the castle. Unfortunately, I'd been there twice already, and that was already two times too many. Nagoya Castle is a reconstruction, and like many Japanese reconstructions, it's now a concrete edifice lacking any charm, soul, or real historical merit. Not only is the entire castle fake, essentially, but it's not even attempting to be an authentic fake; the rooms have all been replaced with lame exhibits on the castle's history and the center is hollowed out with a modern staircase and elevator. Once you pass within the imposing gates, it's a lot like walking around some public library built in the 50's. Sometimes I really think the Japanese have a gift for ruining their own historical sites.